Originally published on 1 May 2020 on CEBM.net

Tom Jefferson, Carl Heneghan

A close examination of the architecture of the hospital (valetudinarium) in the Roman Legionary fortress at Inchtuthil near Perth in Scotland can give us clues as to how we could develop our hospital facilities in the future.

The XX legion built and dismantled the fortress within 3 years, so the buildings were built of wood, unlike the permanent camps on the Rhine which had a similar layout but were built of masonry.

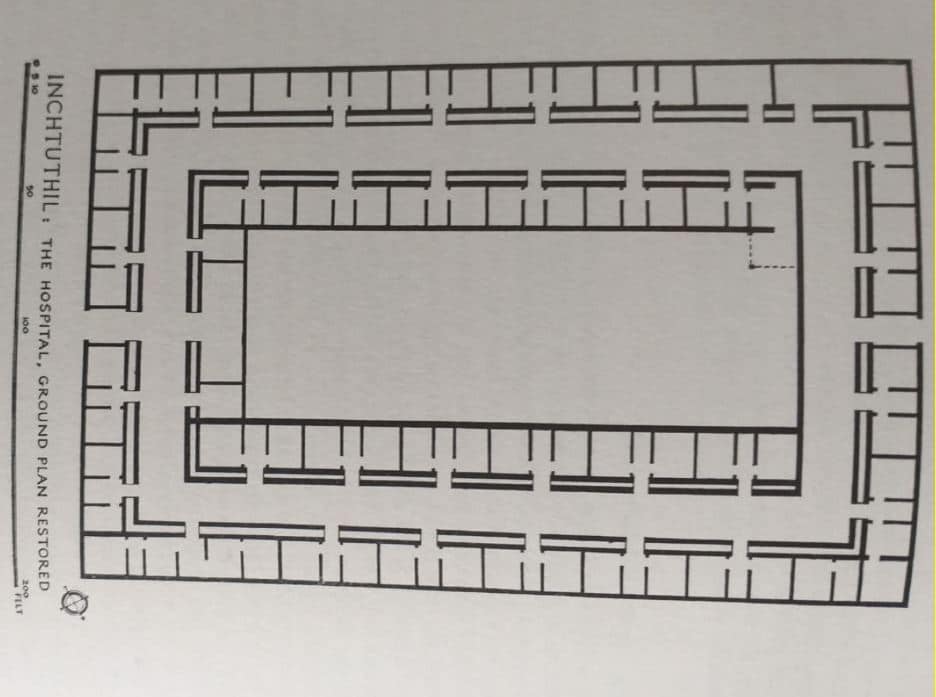

First the plan. The hospital was a single-story rectangular structure with two entrances. These allowed access control and a one-way flow, if necessary.

Two rows of rooms (60 in total) were separated by a connecting corridor, but the outer row abutted the external wall without any communication apart from light and air coming from likely higher up windows.

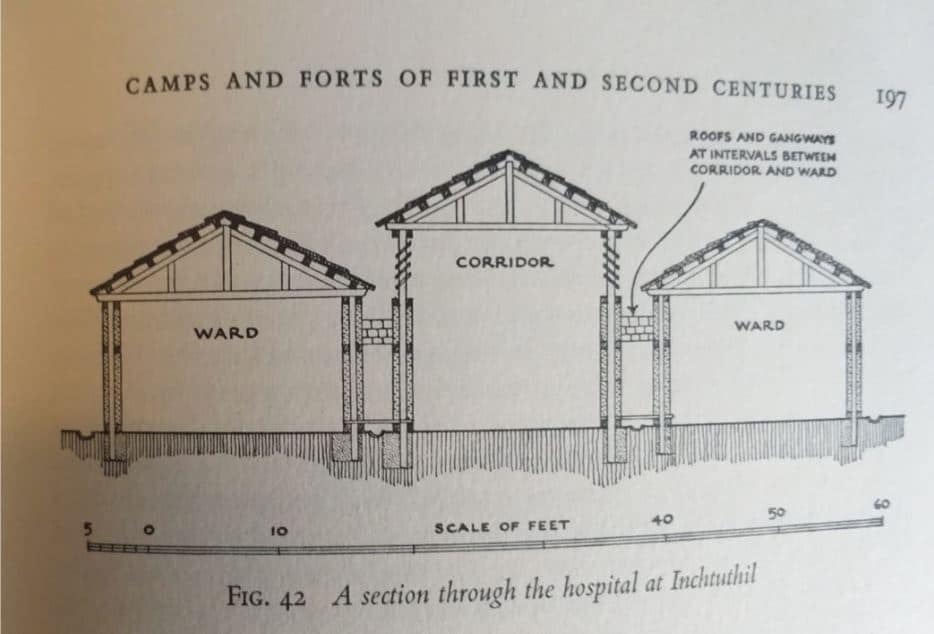

The inner partitions were double-walled to allow air circulation, noise and heat insulation.

The outer row allowed entrances to an inner courtyard where convalescent legionaries could sit in the open air or exercise.

The section layout is also of interest. According to the reconstruction by Sir Ian Richmond and Dr Graham Webster, arguably the greatest experts on the Roman Army, the floors were raised from the ground, especially those of the covered walkways between wards and the connecting corridor.

The separation in rooms had many reasons. In times of surge, there was spare capacity, perhaps up to 5% of the unit strength (around 6000) and distancing or double-bunking would be possible according to need. Also, men from the same century could be accommodated in adjoining cubicles looking after each other, thus helping the medici with their workload. They probably shared a privy and ablutions but there was no common ablution block, unlike post-Crimean War British military hospitals.

Of note that although the structure of valetudinaria is pretty standard throughout the Imperial Army, at Neuss on the Rhine a large room at the entrance was probably used for reception and triage and (in a smaller separate room) sterilisation of instruments and bandages.

The resemblance to the lazaretts of the middle ages is striking

What resonates to our days are simple basic principles of health and hygiene: distancing, air circulation, patient flow control, light, privacy, insulation, buddy aid, maintenance of identity and above all, supreme flexibility in the face of the unknown.

We do not need to climb into a De Lorean car to see the way we should go in treating our fellow human beings.

References

Webster G. The Roman Imperial Army. Adam & Charles Black London 1969

AUTHORS

Carl Heneghan is Professor of Evidence-Based Medicine, Director of the Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine and Director of Studies for the Evidence-Based Health Care Programme. (Full bio and disclosure statement here)

Tom Jefferson is an Epidemiologist. Disclosure statement is here