Originally published on CEBM.net on 8 June 2020

Professor Tim Dixon

Chair in Sustainable Futures in the Built Environment, University of Reading

On behalf of the Oxford COVID-19 Evidence Service Team

University of Oxford

Correspondence to [email protected]

VERDICT

- Urban areas are bearing the brunt of the COVID-19 crisis.

- COVID-19 is having a major impact on the urban poor.

- COVID-19 and the climate change crisis present major opportunities to re-think ‘urban futures’ for cities.

- City visioning, with a strong participatory element, should be part of this process.

BACKGROUND

The COVID-19 crisis has impacted cities throughout the world. The disease’s worst effects are closely linked with urban areas, where death rates tend to be higher because of a complex combination of factors, including population density, national and international connectivity and public health response. In the UK and USA, for example, major urban areas have higher death rates than other types of settlement, and city size has also been found to play an important part in determining infection rates.

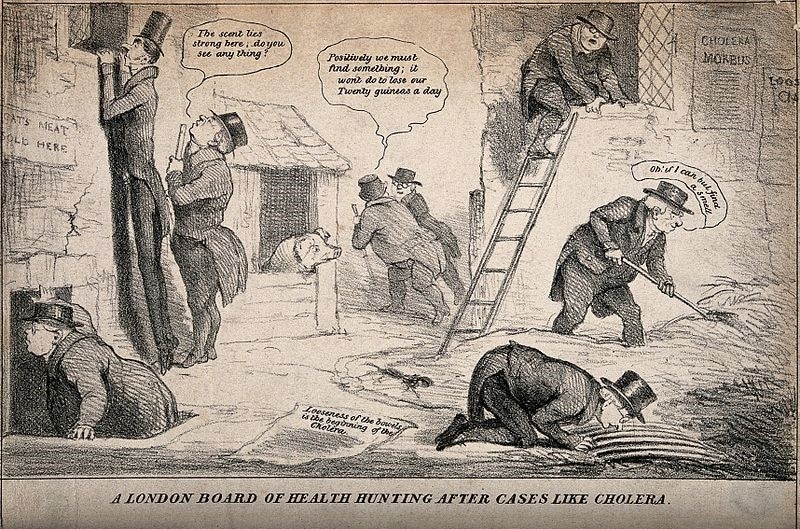

Throughout history, epidemic and pandemic crises (for example, Asiatic Cholera (1826-37) and Spanish Flu (1918-19)) have frequently affected cities, but they have bounced back, often on the crest of rapid economic growth. Often, however, it is the ‘urban poor’ who suffer most in the immediacy of the pandemic – the London Cholera epidemic of 1854, for example, had a substantial economic impact on those living closest to the outbreak for a decade or more. We are already seeing a similar impact with COVID-19 as its effects are forecast by the World Bank to push about 49 million people into extreme poverty in 2020 (Sanchez-Paramo, 2020). City leaders and decision-makers in the global north and the global south therefore face a ‘perfect storm’ of how best to deal with recovery planning and management from COVID-19 alongside the existing pressures of climate change, resource depletion and continued socio-economic inequalities.

WHAT IS THE RESPONSE OF CITIES TO THE CURRENT CRISIS?

Crises also present opportunities for cities, however. Evidence has shown that air quality has improved in cities around the world as economic activity has reduced, vehicle traffic has fallen, and more people work from home. This has also led to a potentially direct and measurable impact on people’s health in cities, as shown by researchers in China. There have therefore been growing calls for a ‘green economic recovery’ from the crisis, and continued focus on a ‘green new deal’ in Europe and the USA, but the danger is that in the rush to boost economic recovery and with oil prices at such low levels, we may yet return to ‘BAU’. However, we are also already seeing city leaders using the lockdown to implement measures which encourage cycling and walking (for example London, Milan, Mexico City, Paris, Bogota and New York) and even ambitions to re-design city economies (Amsterdam).

URBAN FUTURES

Focusing on the global north, this raises the question of what cities might look like beyond the immediate COVID-19 crisis as they start to emerge from lockdown. Could the pandemic change the way cities are designed, and how should they develop in the future? There will be continue to be short-term changes to lifestyle, work and commuting patterns, and what we could increasingly see, and what is more desirable from a sustainability perspective, is that city leaders use the current crisis, for example, to plan and manage for how net zero carbon ambitions will be fulfilled in the longer-term, and how cities can become more sustainable in environmental, social and economic terms. After all, if global warming is to be limited to 1.5 degrees Celsius all cities need to be net zero by 2050 at the very latest. Many cities (currently 1,496 jurisdictions in 30 countries) had already declared climate emergencies before COVID-19 impacted on people’s lives, and, closer to home, in the UK, cities such as Oxford and Reading have not only set out their visions for 2050 but also have climate change strategies in place or under review.

Ultimately net zero carbon and managing a ‘just transition’ remain huge challenges for cities but linking these goals to a new way of thinking about the future (what, in fact, might be termed ‘urban futures’ (Dixon and Tewdwr-Jones, 2021) will be fundamental if cities globally are to become more resilient, more sustainable and smarter in their use of technology. Learning the lessons from COVID-19 must be used to help us increase resilience, and plan and manage for future pandemics and shocks as well. But this will mean building and re-imagining visions for how we want out cities to be by 2030 and beyond to 2050. Bringing key stakeholders (civil society, industry, government and academia) together to ensure these city visions are co-produced and participatory, and underpinned by a roadmap to the future, will be crucial to success.

ADDITIONAL REFERENCE

Dixon, T., Tewdwr-Jones, M. (2021-forthcoming) Urban Futures: City Foresight and City Visions. Policy Press/Bristol University Press.

AUTHOR

Tim Dixon is Professor of Sustainable Futures in the Built Environment at the University of Reading. He is co-leading new research on Thames Valley Live Labs funded by ADEPT/DfT, is co-chair of the Reading Climate Change Partnership, and sits on the industry climate change board for Wokingham Borough Council. He also co-leads the Reading 2050 city vision programme.